Air Force Veteran Beats Breast Cancer

Black Veterans Day Activity Sheet

11/10/2021

Black Americans in the Military: Did You Know These Facts?

11/10/2021The language of advocacy and the ‘unspeakables’ of the Black community

By AMETHYST DAVIS

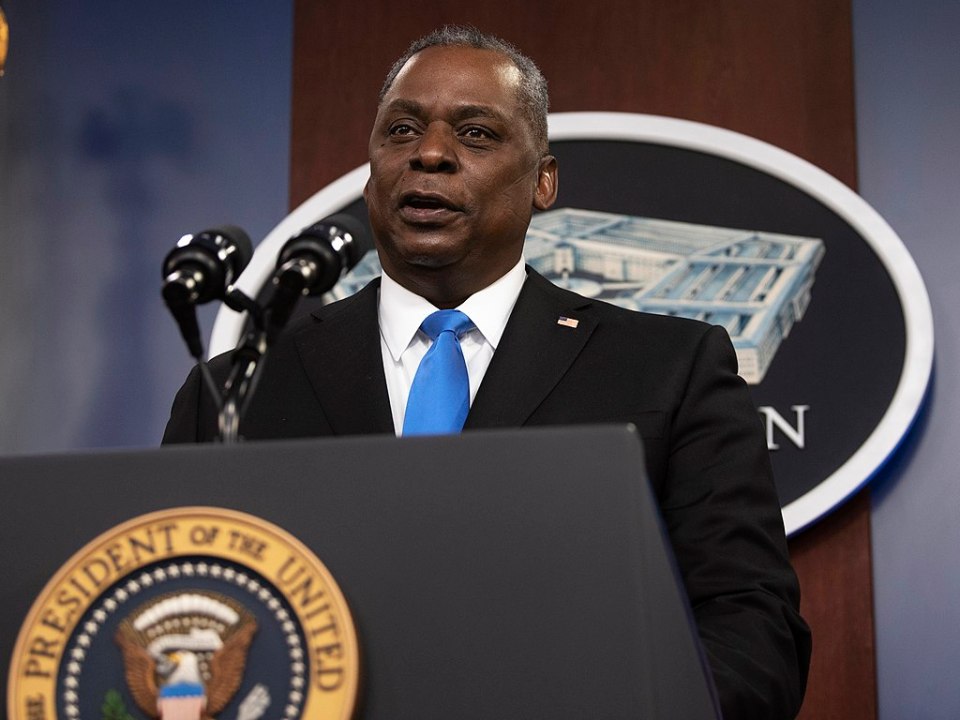

Tanja Thompson and her assistant adjust her camera to make sure it’s at the proper angle. Too high and you’ll get mostly ceiling. Too low and you’ll get the floor. Just right and you capture her bright pink George Mason University sweatshirt and grandiose background.

She sits perfectly positioned between two banners that drape both sides behind her. White flowers accentuate the bright pink, horizontal banners. The word “FAITH” stands out.

It’s her fourth interview this week. “October’s a busy month for me.” Thompson beat breast cancer twice, and regularly speaks with news organizations about her journey. But she wasn’t always so eager.

“I never wanted to do this,” she beams. “I never wanted to do any of this ever.”

The 25-year Air Force veteran was twice diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer. The diagnosis prompted a range of emotions, including shame. But she held onto her faith to find triumph over pain in her journey to help others in the fight against breast cancer.

Thompson, 59, joined the Air Force reserve in 1982, long before the Air Force adopted a formal sexual harassment policy. “I can remember standing on a ladder and a major looked under my skirt.” She started therapy to deal with “the bottom of the iceberg,” the repressed traumas of sexual harassment and assault, she said.

After 25 years in the Air Force, mostly spent in the Washington, D.C., Maryland and Virginia area, Thompson retired in 2007. (Courtesy of Tanja Thompson)

The Fort Wayne, IN, native noted that the Air Force’s culture on sexual harassment — and race — is changing. The #MeToo movement, started to declare an end to sexual harassment and assault, has helped fuel cultural change across industries nationwide.

The Department of Veterans Affairs is the largest provider of cancer care in the United States. Walter Reed Medical Center in Washington, D.C., where Thompson, who now resides in Loudoun County, MD., with her husband, sought treatment, is one of the nation’s premier research centers, and administers healthcare treatment to sitting presidents.

And while the Air Force made strides on sexual harassment, Thompson’s breast cancer diagnosis shows that the nation still has great work to do on reducing disparities in cancer treatment and outcomes.

‘10 Percent’

Black women veterans are slower to receive life-saving surgery as compared to white and non-Hispanic white women in the service, according to a 2019 study from the Journal of American Medical Association. Advancements in treatment have narrowed that gap but Thompson’s story is a testament to the work ahead that remains.

In 2005, Thompson, a mother of three and author of the book “What to Expect When You Weren’t Expecting Cancer,” visited the doctor for her “baseline,” a routine mammogram recommended for women beginning at age 40 to screen for cancer. The results were negative.

Fourteen months later, she returned for another checkup. She was fatigued and had pain in her breast, attributing both to the recent birth of her youngest son and breastfeeding. Her doctor at WRMC, a Black man, recommended she get another screening at the breast center.

She received three tests in one day. Thompson never received a letter from the doctor saying her results were negative. “I never even thought about that letter,” but she received a call to come back to the doctor.

She went by herself.

“I wouldn’t advise anybody to ever do that in life.” Her husband offered to come but Thompson declined. “You only hear 10 percent. You need someone to hear the other 90,” Thompson said.

Her breast cancer diagnosis, HER2 positive, an aggressive form of breast cancer, was numbing. “After those words (‘you have breast cancer’), it was like Charlie Brown,” she said. “All I heard was wah-wah-wah,” she added.

Thompson’s children were all 15 and under when she was first diagnosed, making it even harder to explain her condition to her family.

In the 14 months since her baseline, the cancer was no longer centralized. She had no family history of breast cancer, and yet she had cancerous particles throughout both breasts, baffling doctors. Unable to perform a lumpectomy, they performed a bilateral mastectomy, removing both breasts.

Twice a survivor

The second diagnosis came in 2010. By this time, Thompson was equipped with more knowledge on cancer outcomes. She had reconstruction surgery but kept up with her routine breast exams. So, Thompson knew something wasn’t right when she felt a lump above the silicon of her left breast.

“God talks to us,” she said, and although “it may not be a full conversation,” her faith provided her the inclination to press her doctor, a white woman, to perform a mammogram, MRI, and a localized biopsy — even when they didn’t want to.

All results were inconclusive. “If you’re not an advocate for yourself, nobody else will be.” Thompson was persistent. The doctor perceived her lump to be scar tissue. “Yeah, I said, but it’s not supposed to be there,” Thompson lamented.

After losing her hair to chemotherapy after the second diagnosis, Thompson used the moment to embrace creativity. She dressed up as Avatar the Airbender at a community event in 2010.

A full biopsy that she pushed for revealed not one, but two types of breast cancer. The silver lining, Thompson said, is that scar tissue from around her lump from her first surgery prevented its spread the second time.

Paranoid.

That’s what the doctor wrote in Thompson’s file. “It’s documented.” The physician also mistakenly failed to close her flap after the biopsy, exposing the silicon and risking a possible infection. They provided her ointment for the wound. Thompson’s breast surgeon was appalled at the opening. Thompson later filed a grievance.

Studies show that physicians are less likely to believe Black women who complain of pain compared to their white counterparts. Compassion or empathy should have been expected, Thompson said, because the doctor was a woman.

“I did not let them discount me. […] But I will say, a lot of these doctors don’t have the cultural competency — for military veterans, for Black women.” Some states like California are now mandating medical graduates receive implicit bias training as part of curricula for their state licensure.

Building a support system

“In the Black community, we have what we call ‘the unspeakables.’ There are some things you just don’t talk about.” Sexual assault. Health history. “If someone’s having surgery, you don’t talk about it. You just take care of them.”

Raised in a Black Pentacostal household, Thompson wondered if her diagnosis was a punishment for some wrongdoing.

“Now you have young kids who are trying to figure out is my mommy going to live? Is my brother going to live? Am I going to become an orphan?” she added.

Thompson founded the Breast Cancer Move Foundation, a nonprofit organization that equips breast cancer patients and survivors with cancer screening and advocacy resources. It is hosting several events throughout October, breast cancer awareness month.

It was already hard enough that the military never provided support services for her or her family for either diagnosis (she returned to work several months after both surgeries).

The second diagnosis was particularly hard. Thompson’s youngest son Tysne was receiving liver transplants. Middle child Taylor struggled with mental health seeing his mother sick. Thompson and her husband now talk openly with their children — now all adults — about those years. It’s a form of healing for them all.

Journaling was another emotional release for Thompson, providing the basis for her book. She went to a support group, and decided to use her experiences to help others heal and become self-advocates.

Thompson is a powerful orator. She is routinely sought out motivational speaker, detailing

Her journey in a 2019 TEDxTalk, Tragedy to Triumph.

“If you feel something, if you see something, go say something. […] Navigating (the healthcare system) is just as important to get the things that you need to advance your own healthcare and knowledge of your diagnosis,” she added.

There were three other women also diagnosed at Walter Reed that year, she said. Thompson firmly believes that in the absence of cancer in her family history, her surroundings played a role.

“Rely on medical journals that have been peer reviewed so that you are an informed person,” as opposed to relying entirely upon friends and the internet.

She’s now a motivational speaker and founder of the Breast Cancer Move Foundation, a non-profit organization that helps cancer patients and survivors become a self-advocate as she has.

Thompson also assists companies mediate conflict in the workplace, a growing business as COVID-19 has produced new stresses in the workplace, Thompson remarked. “I have to make time for myself,” she says, balancing the delicate work of pouring into herself just as much as she does to others.

“Conflict is my business!” her website declares. Conflict, resolving it to help others, is at the core of how she’s shaping the next phase of her life.

Thompson will finish her Doctorate of Health Administration at the Virginia University of Lynchburg in December 2021.

Amethyst J. Davis is an NABJ Casey Fellow covering health and COVID-19. She is a proud daughter of Cook County. You can follow her on Twitter @APurple_Reign.

This report was made possible with the support of the Annie E. Casey Foundation.